General Management

The concept of matrices

The Matrix is not just a Hollywood movie, it also features in corporate theatres across many industries. Since Percy Barnevik first coined the term – or gave it initial prominence when restructuring the Swedish-Swiss engineering company ABB – it has been a revenant many times over. Not always for the same reason.

An effective organisation is not over-matricised but it is a more advanced version of painting by numbers. First you need the right numbers, i.e. choose the right people as multipliers, then you need to connect them intelligently, which is where information channels are coming in. The right flow of information is naturally begetting the right processes. It is about creating a naturally effective organisation by aligning and controlling (in a good sense) the flow and placing the points.

Truncated matrices

Often, matrices are introduced in a one-dimensional fashion which is not only a contradiction in itself but as an expression of pure functional lines or as a rule, it is sitting athwart with how processes are supposed to run and products to be developed. If products and processes are actually flowing horizontally, what benefit is a purely functional management structure wearing only the guise of a matrix going to deliver?

When functional reporting is seen as the „real“ reporting, it may resemble a „deep state“ concept, just less effective. Why is it less effective? Because functional reporting is deemed to be deeper but it is inherently narrow and hence fragmentary. It leads to parallelism and a lack of coordination, to complicatedness and inefficiency. So much for the „deep“ function. When different functions come together in projects, they may produce some good work but actually, they resemble a flash mob which may not be enough for systematic (horizontal) product delivery. In this context, watch out for my blog article on the trouble with matrices.

Nash equilibrium and organisational behaviour

Organisations often strive for customer centricity. Generating revenues is of course necessary and focusing on the customer will be both reasonable and laudable. However, customer centricity is more productive and more sustainable when the focusing organisation features stable structures and a balance of (own) interests. This could be described with the economic rather than business term of a Nash equilibrium – keeping everybody happy. However, this does not work in real corporate life because of moral – or shall we say mental – hazard.

It’s money that matters

For instance, is it possible to take pay off the radar?

Heretical thought

To some extent it may be possible to achieve progress in this direction, albeit it will never be perfect – and it may be expensive at least on the way in. The higher the echelons of management, the harder it becomes to disprove Pavlov. Variable reward schemes make sense to some extent but they come with downsides. In a number of cases, inherent greed appears like a self-deceiving mirage emanating from the position at the top. It could be paraphrased as a ‚perverted Cartesian‘: „I am (the boss), therefore I think (better than others)“, forming the basis for a self-aggrandising sense of entitlement.

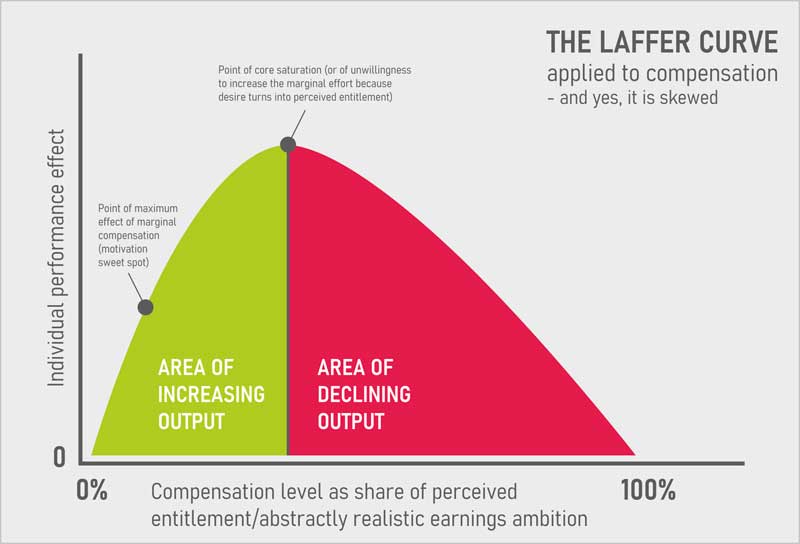

A Laffer curve on compensation?

Arthur B. Laffer used his curve to describe the decreasing tax revenue if the tax rate is set beyond the optimum level. This could also apply to Compensation. The more people are paid, the more they perform but only up to a certain limit. This is primarily inherent to top manager’s own productive aptitude and secondly their ability to amplify and multiply it through the organisation. However, a number of them end up losing focus and the wisdom to restrain themselves. Modesty or the rare phenomenon of humility go out of the window. This should normally lead to management’s productivity diminishing. Due to their position, it does not just plateau, it actually goes down, turns negative. Questioning oneself without becoming eternally despondent or even desperate could be an answer but this requires really rare qualities. These are normally only acquired by a formidable formation of character and this in turn is achieved through failures. The trouble is that people who have failed late enough in life to understand but early enough in their career to learn from it hardly ever make it to the top. This could be the mirror image.

People vs processes

A common wisdom is to establish processes irrespective of the people and make people suit the processes. Processes are the framework supposed to provide stability beyond people’s fluctuation. This is why they are supposed to take precedence and are usually designed without regard to the people who are meant to apply them. This is not ideal. On the other hand, relying on people’s ingenuity or improvisation would introduce a level of unsystematic variation and hence uncertainty, i.e. risk which is rightly unwanted and would hollow out any organisation.

Yet on balance, churning people looks like the costliest option. It is not just the implementation of a separation process but more the cost of having people leave. Often, some of these costs are semi-apparent in soaring consultants‘ bills to plug the holes („of course, management have done all they could to stabilise“) – but in effect, this is fire-fighting rather than building the organisation fireproof) – other costs are hidden like the loss of corporate memory, level of engagement, etc. Management can only sort-of-control the quantity of skilled labour done but hardly the quality unless such is blatantly obvious. The more skilled the labour, the shallower the control. Fact.

What is the solution?

- Design processes ‚bottom up‘ i.e. start with the people (not to mention that attracting and selecting the right people – plus keeping them (right) – is the essence of any successful organisation).

- Have due regard to the practicability and the discernible reasonableness of processes. People and processes are a bit like a couple in a marriage: a certain degree of attractiveness makes living together easier – and again as in marriage, divorce is costly.

Heretical thought

It’s not only shit that flows downhill, it is also incompetence, or more accurately, its effects. Key multipliers in a good organisation must be competent, intellectually and in their behaviour (it is fair to assume a correlation of at least 0.5 between these two parameters). Not the drive for self-preservation but rather the absence of management’s perceived need of asserting themselves usually proves a boon to any organisation.

Confucius wrote of „good“ government as virtuous government. The same holds for management. Outside a purely mercenary organisation, only a somewhat virtuous management is credible to a corresponding extent. Without credibility, management is ineffectual unless they are relying on fear and practical coercion. These tools however do not work in most places and they never work for a long time. Ultimately, it is only credibility that counts and credibility in turn rests on veracity and authenticity. Grand theatrical performances can easily backfire if they lack authenticity – personal and factual authenticity.

Change management

„Things must change for everything to remain the same“

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, ll gattopardo

What actually is Change Management?

I have always wondered what a team or department – or even an expert concerned with and labelled as „change management“ is supposed to look like. Knowing how to implement change sounds reasonable but what does it mean in fact? Is there a one-route-for-all path to change? Hardly. Change management is managing progress towards an objective – a vision which is broken down into concrete, tangible and achievable components. Actually, management which is statically administrative only is no management at all, just caretaking. In order to move towards an objective or target operating model, you need first understand it, its substance, background, setup options and the regulatory or legal context. Add customers, products and technology and you have a demanding task.

Change managers might know how to fly a plane but without the expertise in navigation and maintenance, it will not take off. The coincidence of knowledge, reason and purpose is essential once more. This requires the right mix of breadth and depth in the teams and in particular in the leaders of change because there will be choices to be made which require knowledge – and the leadership skill of keeping track of the purpose. Change management magnifies the task of coping with Porter’s five forces and sometimes the four horsemen, too. These come in the guises of ignorance, inertia, narrow career interest and personal vanity.

Newton’s first law of motion:

„An object at rest remains at rest, and an object in motion remains in motion at constant speed and in a straight line unless acted on by an unbalanced force.“

Change needs volition

If you do not like the place of the object, i.e. the organisation and its products and the direction or speed of travel, you need to apply some force to change it. This requires volition. Volition is more than and different from motivation. Motivation is good and sufficient to keep on track but to change t(r)ack, volition is what is needed. The term was discredited due to its role in the totalitarian world view of some of the most infamous regimes of the 20th century but this does not change its substantial relevance in psychology – not just of the masses but also of big organisations. In small organisations, the efficacy threshold for volition is lower because complicatedness is less pronounced and there are fewer layers of people who seem busy with anything else but not with progress. Big organisations usually sport many positions that are self-sufficient but do not produce a clearly visible contribution. Sometimes this is deceiving and closer scrutiny reveals such contribution or at least the potential for it, in other cases a value proposition is not in sight at all.

If change needs volition, this is the essential tool – but volition does not feed itself – it needs a vision in turn. It is difficult to develop this vision in complex organisations. I am talking about a vision which is substantial and broadly consistent. From there, other parameters are delineated. Motivation is one of those. Volition engenders a vision and provides orientation. Motivation is a smaller but indispensable tool helping to achieve the vision. Motivation feeds on many strands; recognition is an important one. If it shall not be hollow and fake, recognition means recognising differences – and motivation conversely falls by the wayside where differences in performance are ignored (see also www.instagram.com/maschmeyer (in German).

Change is a journey

It is natural as well as it is crucial that volition begets a vision of the final objective but it is equally important that this vision is substantial, concrete and consistent enough to be broken down into phases and steps – and concrete action. In other words, if the vision lives on the loft, there needs to be a building below it, built on firm ground or the realistic assessment of the status quo, present capabilities and available resources. The most important part of this building would be the staircases.